CONTINUED FROM THE PRINT EDITION:

How Oregon almost became Canadian, eh?

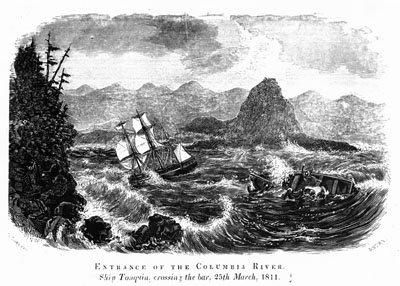

His job was to bring a large cohort of passengers — mostly partners, whom Astor was paying for their services with a slice of the business, along with a number of French voyageurs and clerks and clerical workers — around to the new colony. Thorn got off to a bad start right away by trying to impose an 8 p.m. curfew on the partners. Thorn, the Navy officer and ship captain, saw mutiny and insubordination in nearly everything these mountain-man fur traders did; they in turn considered him an employee. Things reached a head when the ship stopped at the Falkland Islands to refill its water casks. While a big party of the partners were ashore on the treeless, foodless island, Thorn weighed anchor and tried to maroon them there, apparently figuring Astor would be well rid of such unruly dopes. Fortunately for the marooned men, one of their friends pulled a pair of pistols and told Thorn, “Turn back, or you are a dead man this instant.” The ship got to them just in time, as the marooned men had been pulling after the ship in their rowboat; they’d just broken an oar and were well on their way to being swamped in the open sea. When the Tonquin arrived at the mouth of the Columbia, Thorn ordered his first mate, Mr. Fox, whom he was feuding with because Fox had befriended some of the passengers, to launch a rowboat and sound out the channel across the bar. It was tantamount to a suicide mission, as the seas were very high. Thorn staffed the boat with voyageurs, risking only Fox and one other sailor from his crew. The boat got not far from the Tonquin when the signal flag was waved in a distress call. Thorn ignored it, and soon it disappeared, along with all its occupants. The boat was never seen again. Another boat was launched after the seas had quieted a bit, but failed to find the channel. Then a third boat did find the channel, but Thorn, his thirst for blood apparently not yet fully slaked, sailed straight past the boat and into the bar, making no attempt to stop for or even throw a rope to his benefactors. They had to make their way ashore as best they could. Two of them, against all odds, actually survived. There, in Baker Bay, the company men disembarked with their trade goods and supplies to build Fort Astoria. Then Thorn sailed the Tonquin out to do some trading among the Indians. For his first foray into trading for sea-otter pelts, Thorn put into a little cove on Vancouver Island. There, he attempted to impose his Navy discipline on a First Nations chief, barking out an unacceptably low price in blankets and knives and getting angry when it was not immediately agreed to. Finally, without having budged on his price, he seized the chief and threw him ignominiously overboard. The next morning, the Indians returned to the Tonquin, accepted Thorn’s price, and started trading. But, just as Thorn was probably starting to think he’d cracked the code for negotiating with Indians, one of their leaders gave a signal, and they whipped out knives and war clubs to avenge the insult to their chief. The next day, the sole survivor of the attack touched off the powder magazine, and that was the end of the Tonquin, along with a great many Natives who had climbed aboard to explore their prize. But a good deal of damage had been done. Thorn’s bargaining style had not only cost the expedition its ship and stranded Fort Astoria in the wilderness, it had sent a really powerful message that the “Bostons” were dangerous and untrustworthy. Other American traders kept reinforcing this message — one signed the death-warrant of the Astorians’ whole upriver trading operation by having an Indian lynched for stealing a goblet even though the Indian returned the goblet when asked about it. Stranded in Fort Astoria, one of Astor’s partners, Duncan McDougal, became convinced the Indians would soon turn on them and slaughter them. The crafty McDougal headed this off by pretending to have a “bottle of smallpox” which he would uncork if attacked. Whether this kept an Indian attack from happening or not is debatable — McDougal was himself a devious schemer, so he was always on the lookout for evidence that others were scheming against him — but it certainly didn’t make the Astorians more popular and it did little to shake the growing impression among the local tribes that the “Bostons” were just too unpredictable and dangerous to do business with. That included selling them fish and venison. The Indians, who had flocked around the fort to trade when the Astorians first arrived, now disappeared into the woods. They seemed to be actively avoiding contact. It was going to be a hungry winter.

For Blackfeet, stealing horses was a lark. Killing someone for stealing a horse, to them, was like hanging the kid who painted the town water tower John Deere green. Lewis made it infinitely worse by hanging a Jefferson Peace Medal around the neck of one of the corpses. After that, Blackfeet became implacable enemies to not only American traders, but Spanish, French, and British as well. So the Astorian party had to find a way west that didn’t cut through Blackfeet country. They actually did pretty well for about the first two-thirds of the journey, although their leader, Wilson Price Hunt, seemed not to understand the need to hurry so that winter would not catch them in the mountains.

|